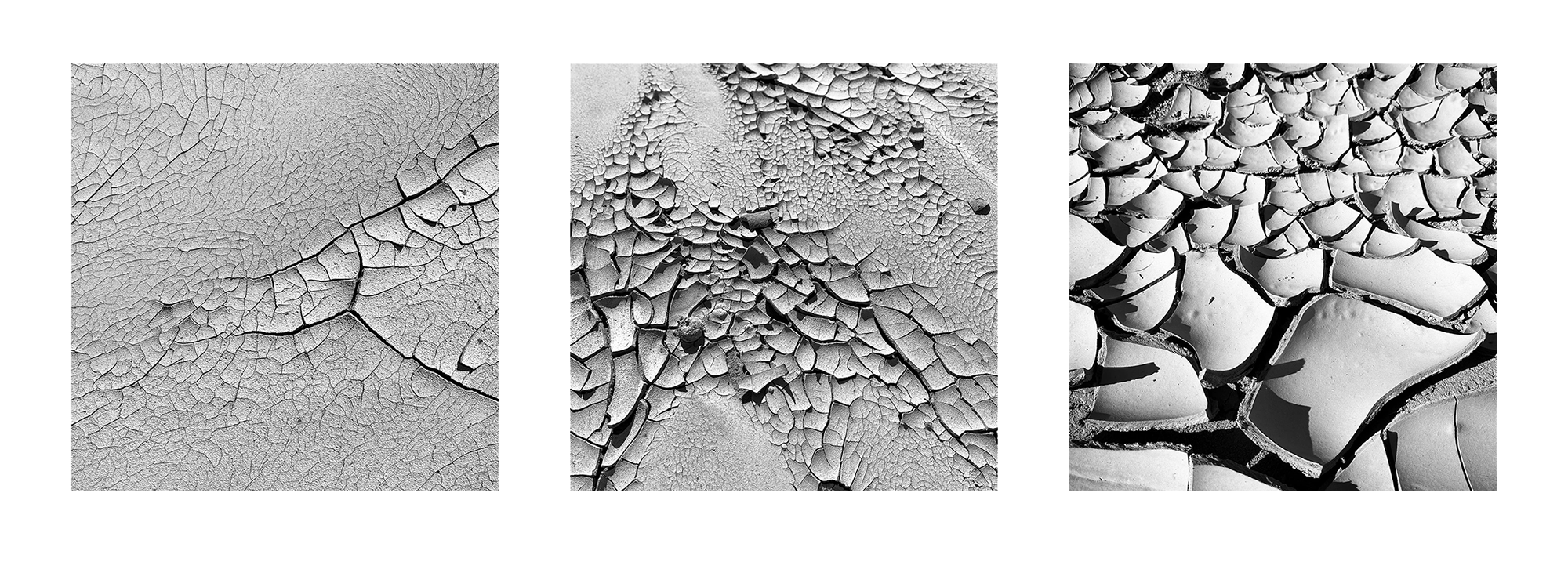

Benn Colker returned from a recent visit to Cayuma Valley with a collection of dirt. It was not the geological composition that he found interesting, but rather the way a typically cohesive surface had become a group of distinct (and unusual) objects. Benn prompted the Bureau’s departments to capture the essence of one particular “dirt curl” with an interpretation or object pairing from the collection.

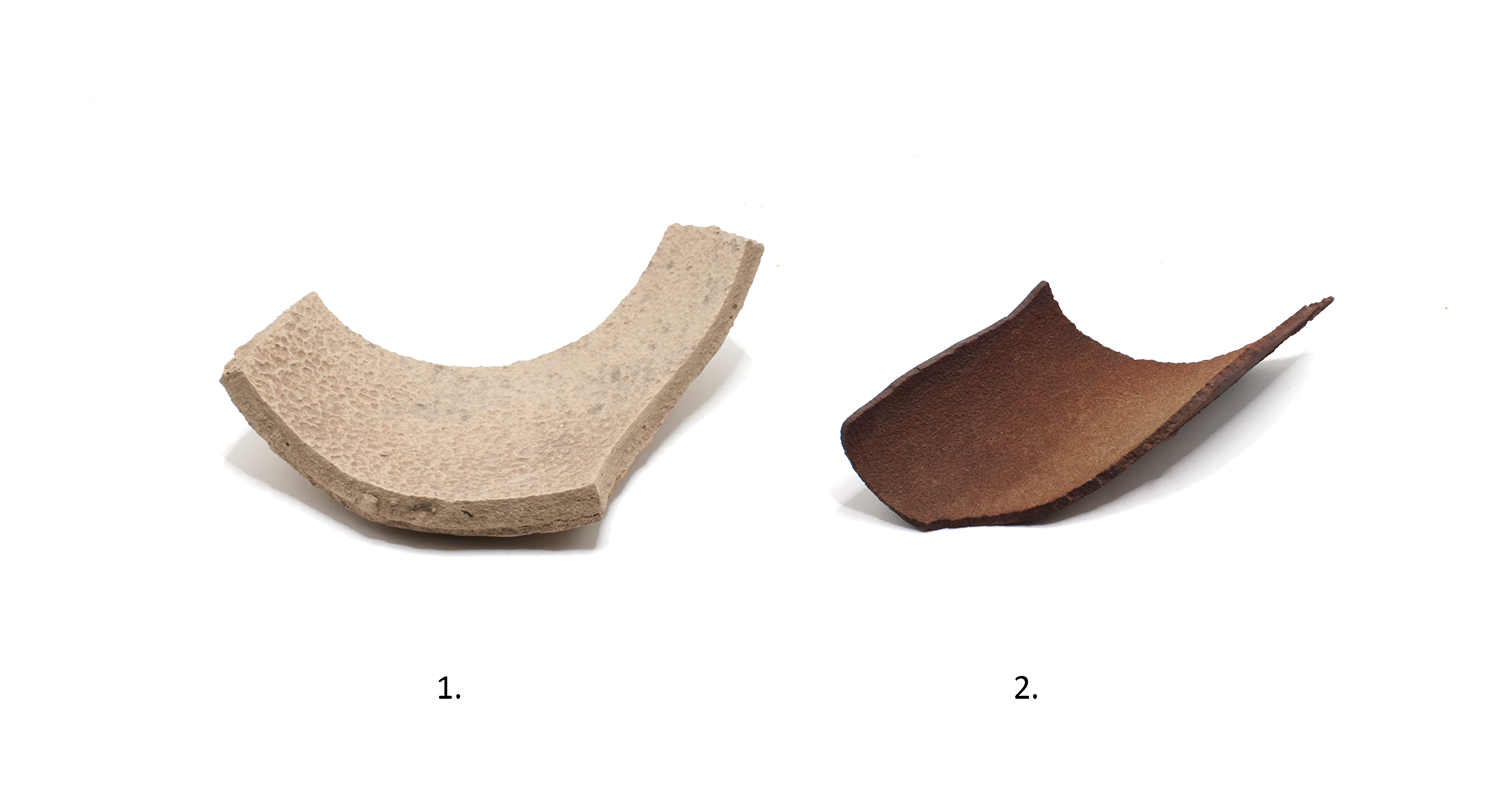

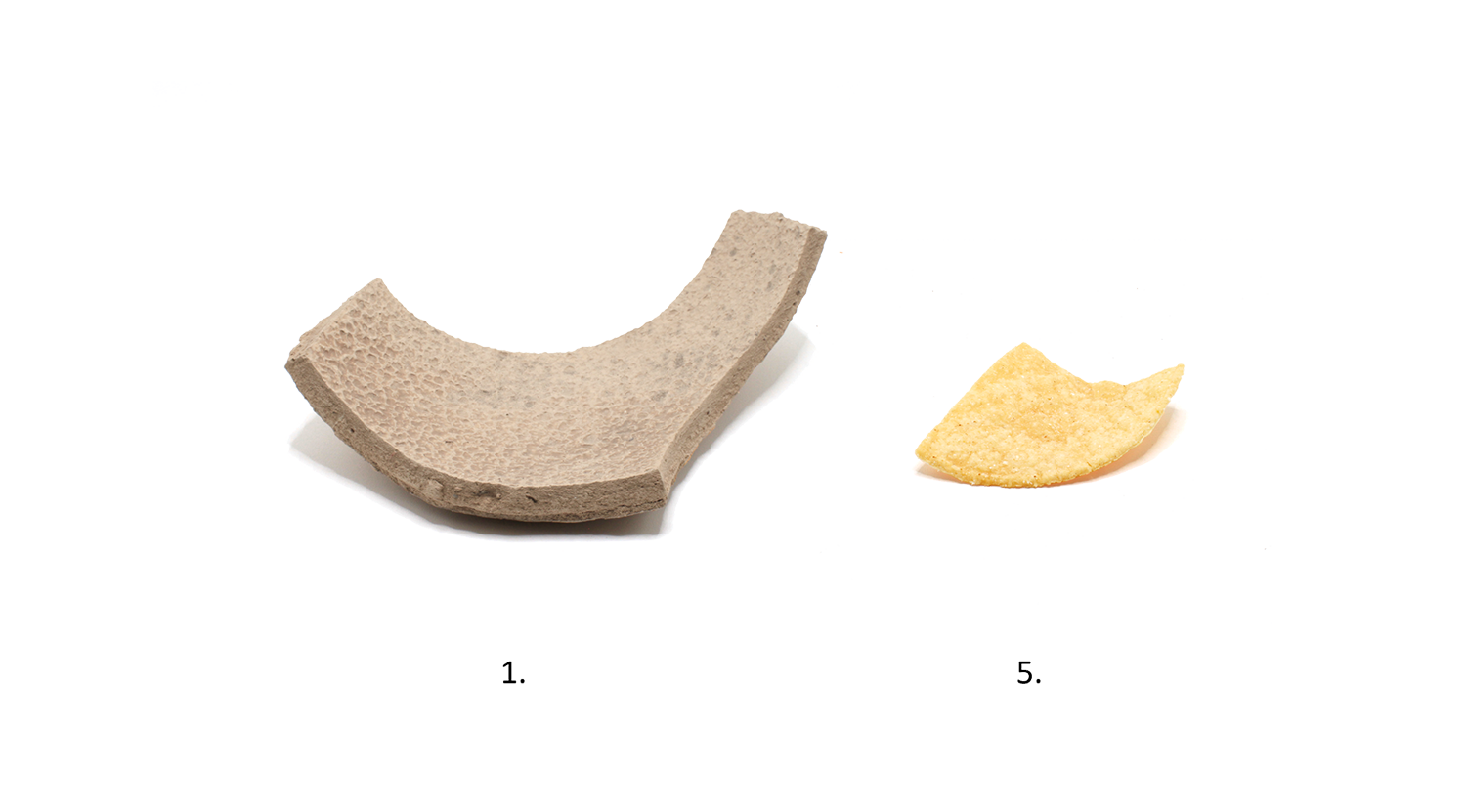

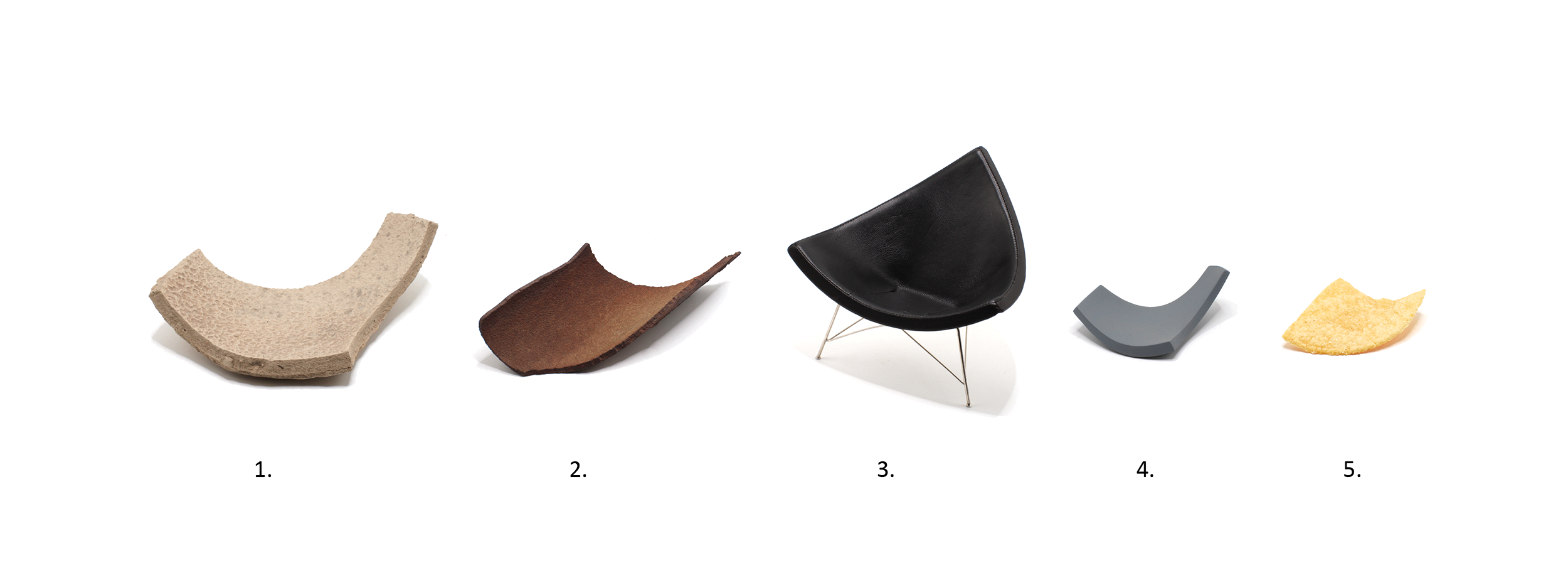

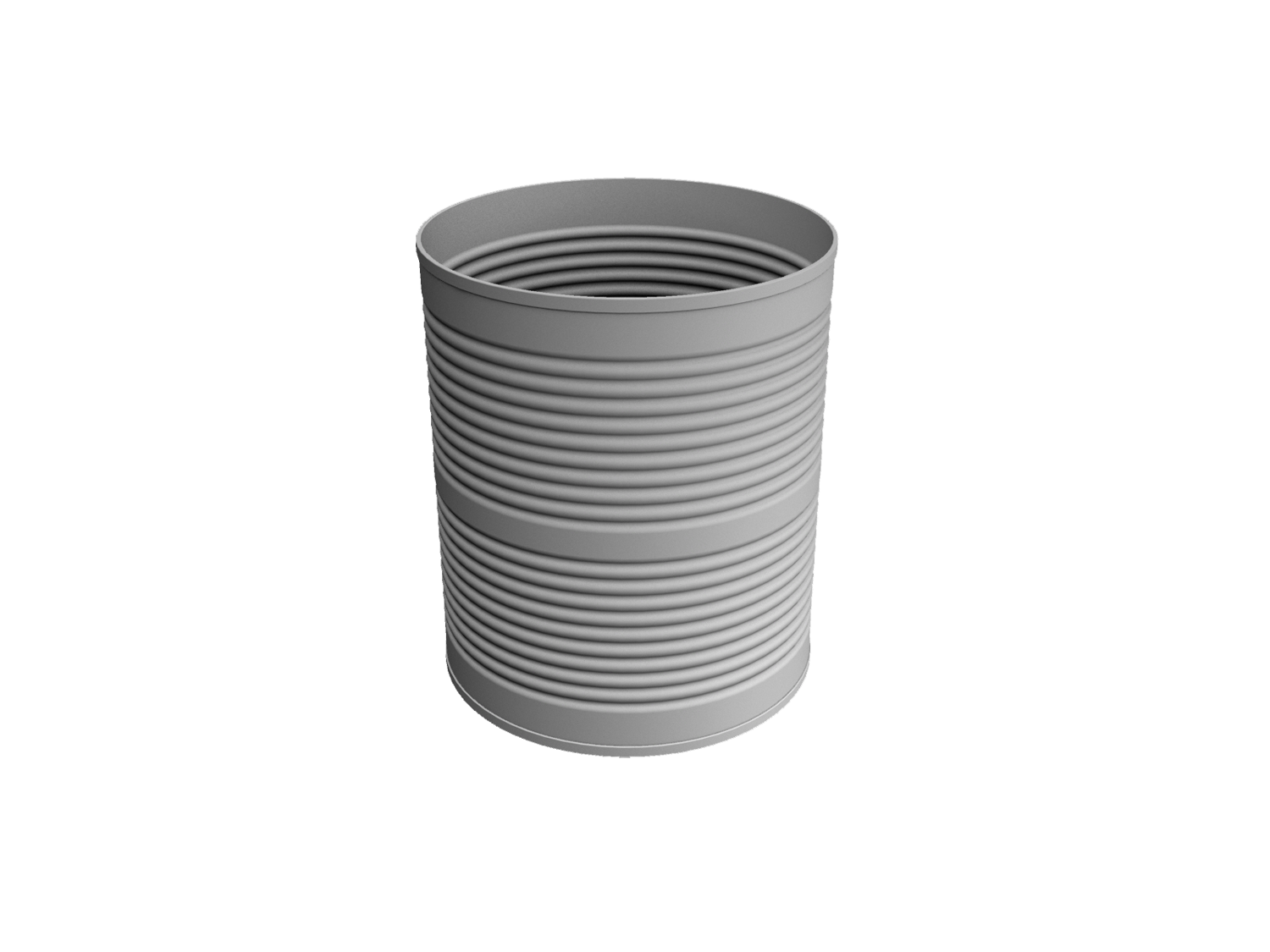

Martin Vesper from the Department of Matter proposed specimen 2 (below). The resemblance was clear, and as a broken remnant of a cast iron pipe, its history facilitating the movement of water offered a connection back to the submerged origins of the dirt curl.

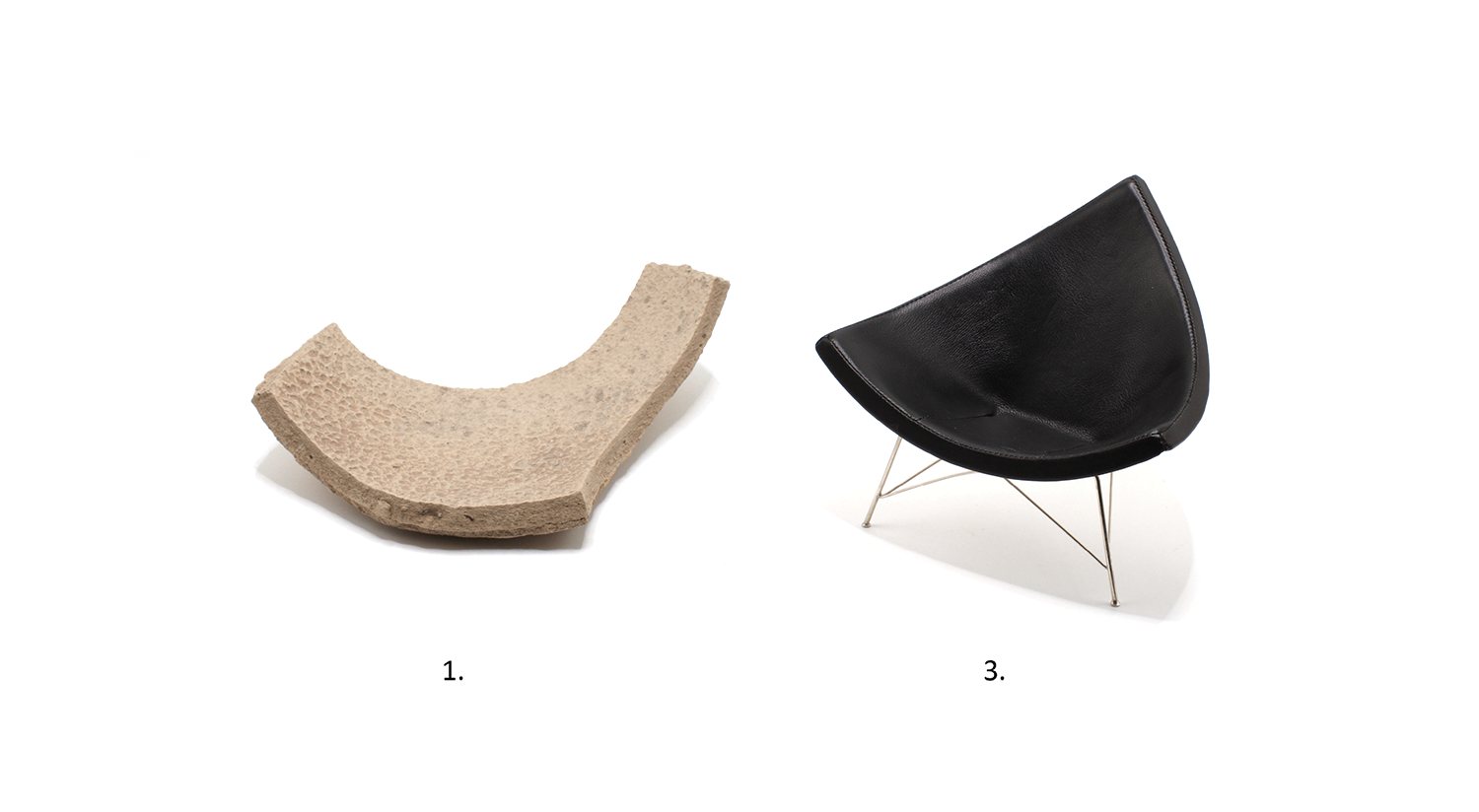

However, Jackson Witcombe from the Department of Form was deeply unsatisfied with this pairing. Describing the dirt curl’s geometry as a portion of a cylinder was, in his mind, a gross oversimplification. The curling geometry was created from a much different network of curves and its surface was extruded to a greater thickness. Jackson responded by paring the dirt curl with a 1 to 6 scale replica of George Nelson’s Coconut Chair (specimen 3, below).

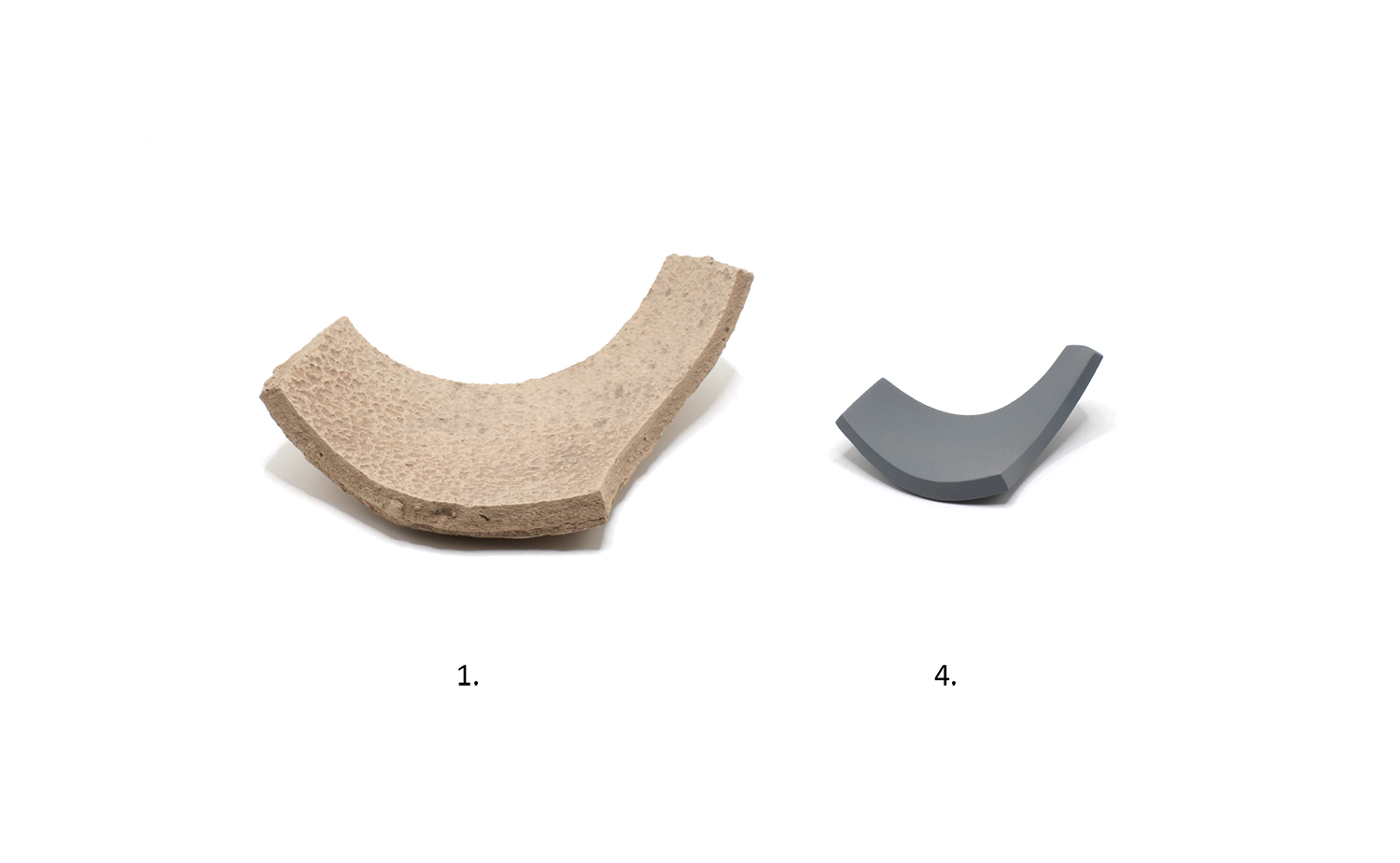

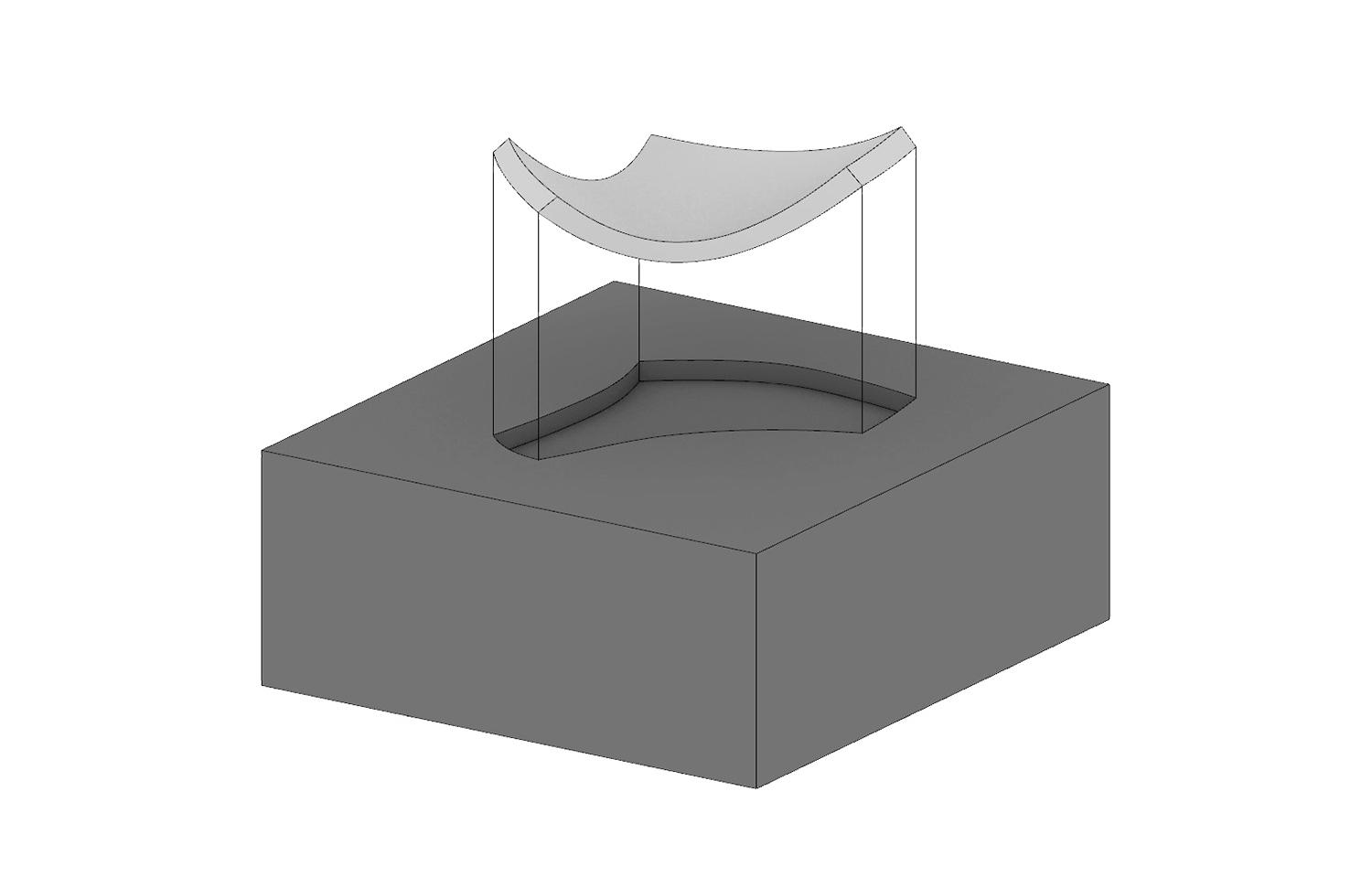

However, Eva Aivars from the Department of Form saw this paring as yet another troubling oversimplification. She pointed out that as the curl was curling, portions pulled away from the earth below at different rates, creating an asymmetrical curvature. To illustrate these nuances, Eva took precise measurements from the dirt curl and modeled its geometry in virtual space, then 3d printed the form to return it to the physical world (specimen 4, below).

However, Vince Maitland from the Department of Matter dismissed these geometric studies. Capturing the essence of the dirt curl was not about describing smooth curves, regardless of how accurately they had been documented. Irregularity and unpredictability were integral to the dirt curl. For Vince, as usual, the key was understanding the forces behind an object’s creation. This dirt curl was a snapshot of process frozen in time and the forces were changing moisture content, air flow and heat. As it turns out, all of these forces manifest perfectly in a tortilla chip (specimen 5, below).

The debate continued long into the evening with no agreement between departments - except that the tortilla chips were delicious.